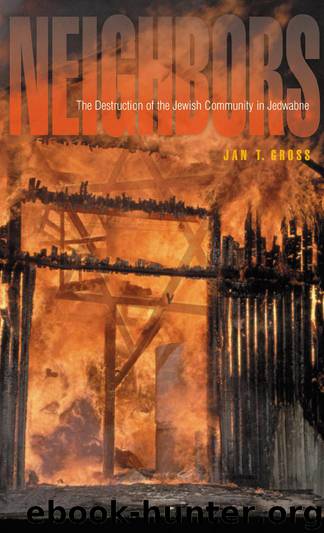

Neighbors by Jan T. Gross

Author:Jan T. Gross

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2001-10-20T16:00:00+00:00

COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITY

Even though the Nazi-conceived project of the eradication of world Jewry will remain, at its core, a mystery, we know a lot about various mechanisms of the “final solution.” And one of the things we do know is that the Einsatzgruppen, German police detachments, and various functionaries who implemented the “final solution” did not compel the local population to participate directly in the murder of Jews. Bloody pogroms were tolerated, sometimes even invited, especially after the opening of the Russo-German war—a special directive was issued to this effect by the head of the Main Reich Security Office, Reinhardt Heydrich.1 A lot of prohibitions concerning the Jews were issued as well. In occupied Poland, for example, people could not, under penalty of death, offer assistance to Jews hiding outside of the German-designated ghettos. Though there were sadistic individuals who, particularly in camps, might force prisoners to kill each other, in general nobody was forced to kill the Jews. In other words, the so-called local population involved in killings of Jews did so of its own free will.

And if in collective Jewish memory this phenomenon is ingrained—that local Polish people killed the Jews because they wanted to, not because they had to—then Jews will hold them to be particularly responsible for what they have done. A murderer in uniform remains a state functionary acting under orders, and he might even be presumed to have mental reservations about what he has been ordered to do. Not so a civilian, killing another human being of his own free will—such an evildoer is unequivocally but a murderer.

Poles hurt the Jews in numerous interactions throughout the war. And it is not exclusively killings that are stressed in people’s recollections from the period. One might recall, for illustration, a few women described in an autobiographical fragment, “A Quarter-Hour Passed in a Pastry Shop,” from a powerful memoir by Michał Głowiński, today one of the foremost literary critics in Poland. He was a little boy at the time of the German occupation. On this occasion an aunt had left him alone for fifteen minutes in a little Warsaw café; after sitting him down at a table with a pastry, she went out to make a few telephone calls. As soon as she left the premises, the young Jewish boy became an object of scrutiny and questioning by a flock of women who could just as well have left him in peace.2 Between this episode and the Jedwabne murders one can inscribe an entire range of Polish-Jewish encounters that, in the midst of all their situational variety, had one feature in common: they all carried potentially deadly consequences for the Jews.

When reflecting about this epoch, we must not assign collective responsibility. We must be clearheaded enough to remember that for each killing only a specific murderer or group of murderers is responsible. But we nevertheless might be compelled to investigate what makes a nation (as in “the Germans”) capable of carrying out such deeds. Or can atrocious deeds

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31940)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19083)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14389)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12026)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5369)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4918)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4780)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4604)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4532)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4478)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4211)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4109)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4098)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3965)